In the Line of Fire: The IEA Is Right Where It Should Be

The IEA is right where it should be, and as a result, the agency may just have to take some bullets to do its duty of informing policy makers.

Conservative critics in the United States are up in arms about the International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy analyst Robert McNally frames it as a “climate-obsessed non-governmental organization (NGO).” Senate Majority Whip John Barrasso (R-WY) judges the agency to be “biased” and accuses it of “gambling with the world’s energy security.” Former IEA staff member Neil Atkinson calls its work “at best, distorted and, at worst, dangerously wrong.”

This critique of the IEA from the right follows a decade of carping from the left. The agency’s spot in the line of fire may not be comfortable, but it’s actually a good sign. The IEA is relevant enough to be worth criticizing and impartial enough to receive incoming fire from both flanks.

That’s not to say that the IEA should take a victory lap. The conservatives, like the progressives, make valid, as well as gratuitous, points. In the context of the Trump administration’s withdrawal from international organizations of all stripes and congressional budget cutting, the agency needs to respond constructively to these critics. Doing so will help preserve a vital international function, as well as the United States’ global influence.

What is the IEA?

The IEA was founded in 1974 at the insistence of U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The Arab oil embargo had exposed advanced industrial countries’ vulnerability, contributing to the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression. Based in Paris, the agency sought primarily to foster collaboration among major oil-consuming countries to avoid future shocks and manage crises. It also became an authoritative resource for energy industry data, lubricating market operations.

Global energy markets were transformed over the ensuing decades. Demand from China and other emerging economies surpassed that of the West. (Figure One) The shale gas revolution propelled the United States back to a leading role as a supplier. While the price of gasoline remains a political flash point, the impact of energy market volatility on the economies of the United States and its allies diminished dramatically.

Figure One: Top Five Petroleum Importing Countries, 1974 and 2014 (Million Barrels/Day)

| Rank | 1974 | Imports | Rank | 2014 | Imports |

| 1 | Japan | 4.8 | 1 | USA | 6.2 |

| 2 | West Germany | 4.1 | 2 | China | 6.2 |

| 3 | USA | 4.0 | 3 | India | 3.8 |

| 4 | France | 2.6 | 4 | Japan | 3.4 |

| 5 | Italy | 2.4 | 5 | South Korea | 2.5 |

Table created by author. Data from United Nations Comtrade Database. Accessed January 15, 2025.

A New Mission: Climate Change

The IEA, by some lights, had worked itself out of a job. But a new challenge was rising on the global agenda: climate change. Other international bodies established that unabated fossil fuel combustion was the primary cause of the problem. Few were as well-suited as the IEA to delve into what to do about it.

The IEA seized this opportunity in 2015. Under U.S. leadership, the national energy ministers who comprised its governing board approved an expansion of its mandate to “energy security beyond oil,” engagement with major emerging economies (which were not OECD members), and a greater focus on clean energy technologies. IEA veteran Fatih Birol developed the strategy in light of the Paris climate agreement, which was signed in the same year, and led its implementation as the agency’s new executive director.

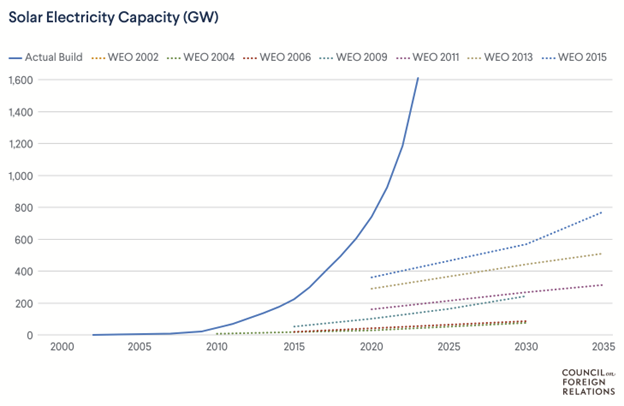

The IEA’s 2015 change of course responded to a threat as well as an opportunity. Critics from the left regularly complained about the agency’s underestimation of the growth of renewables, especially solar power. Graphs demonstrating the dramatic divergence of the actual path of solar deployment from the trajectory in IEA’s baseline scenario became the left’s favorite meme. (Figure Two)

Figure Two: Global Solar Power Capacity Projections in IEA’s World Energy Outlook (WEO) Current Policies Scenario (Dotted Lines) Compared to Actual Build (Solid Line)

Table created by author. Data from International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook, various years. Accessed April 2, 2025.

The critique took a concrete form with the founding of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in 2009. Some European nations, led by Germany, viewed the IEA as advocates for fossil fuel and nuclear power. IRENA not only seized a lightly-held piece of IEA’s turf, but its membership was open to all countries, not just the rich ones. It quickly grew to more than 160 members. By 2016, IRENA, with core financial support from Germany and the United Arab Emirates (which hosts its secretariat), had carved out a distinctive role in support of international climate diplomacy.

The IEA’s initial response manifested in 2017 in a new Clean Energy Transitions Program. Funded through voluntary contributions, this program works with individual countries (whether IEA members or not) to develop action plans to progress toward net-zero emissions — a significant broadening of the agency’s capabilities.

The pivot came to full fruition in the 2020 edition of the IEA’s flagship publication, World Energy Outlook (WEO). This report substituted “stated policies for “current policies” in its baseline scenario and introduced an ambitious scenario that would achieve net zero emissions by 2050. (I delve more deeply into these scenarios below.) It also included a far more optimistic treatment of solar power. As Simon Evans noted in Carbon Brief, “renewables account for the majority of demand growth in all scenarios.”

Less than eighteen months after defining this new profile, however, the IEA’s original mandate soared back to prominence. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 threatened “calamity,” in the estimation of Columbia University’s Jason Bordoff and Harvard’s Meghan O’Sullivan. The world’s dependence on a wide range of Russian energy resources, especially Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas, exposed vulnerabilities that had been neglected since the 1970s.

Consistent with its mandate and led by the United States, the IEA coordinated the largest release of emergency oil stocks by its members less than a week after the invasion began. Another release, doubling the previous record, followed within a month. In June 2022, Ukraine officially affiliated with the IEA, and the agency initiated a work program to help the country cope with ongoing Russian attacks on its energy infrastructure.

The reemergence of energy security did not impede the IEA’s pursuit of its climate change mitigation mandate, however. In fact, the mandate was further expanded by the governing board in 2022. The adoption of an ambitious climate policy by the United States, the IEA’s most important constituent, undoubtedly encouraged this strategy.

The Conservative Backlash

However, a backlash was brewing in American opposition circles. Former Trump administration official Bernard McNamee in 2023 characterized the IEA as “unrealistic and politically oriented” in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 volume. McNally published his critique in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece in February 2024. Senator Barrasso and House Energy and Commerce chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) took up the argument in a letter to Birol a couple of months later.

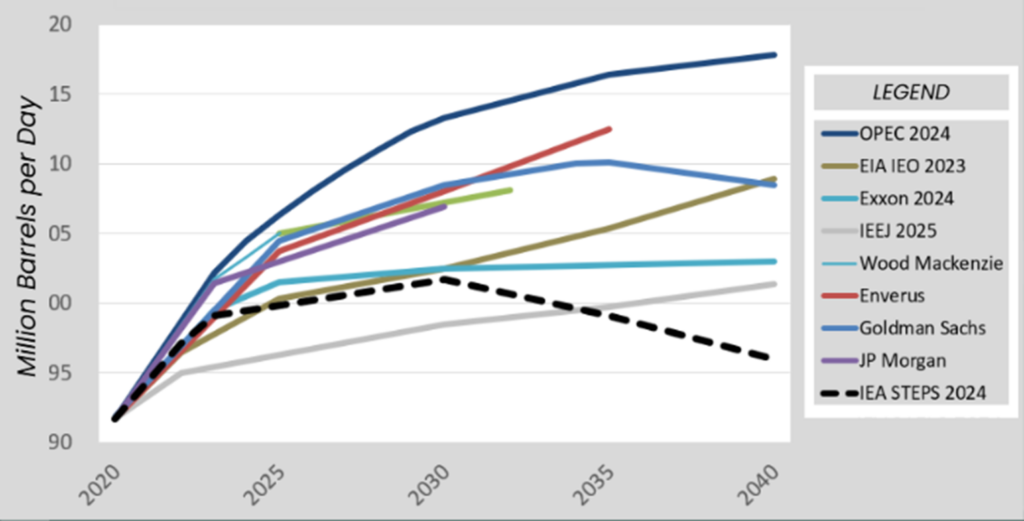

A December 2024 report from Barrasso’s committee staff lays out the critique in full. It views IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario as guesswork that is “tailor made to discourage investment in oil and natural gas.” The report offers an alternative meme comparing oil demand in this scenario to those of others. (Figure 3) The Net Zero Emissions Scenario gives readers “the false sense that deep emissions cuts will be neither difficult nor expensive.” In sum, IEA has “lost its way” as it “lists to port.”

Figure 3: Oil Demand Projections in IEA 2024 Stated Policies (STEPS) Scenario and Those of Other Organizations

Image courtesy of the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Author is Senator John Barrasso. Public domain.

With the Trump administration in power, and Republicans controlling Congress, the critique could pack a real punch. The United States government provides twenty-three percent of the IEA’s regular budget and fourteen percent of its total budget, (about $7 million per year) according to the Barrasso report. It seems likely that the administration will seek to redirect the IEA, and it could reduce U.S. support, financial or otherwise, or even withdraw from membership. At a minimum, the administration is sending mixed signals by supporting India’s pioneering bid for full membership, which would require sustained engagement, even as some officials echo conservative talking points.

The gaping hole in the conservative critique is obvious. Climate change is occurring, is caused primarily by unabated combustion of fossil fuels, will intensify much more if national governments fail to take action to address it, and will impose substantial harm on people and ecosystems. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states these conclusions with “high confidence.” The Barrasso report has only this to say: “Climate change is an extraordinarily complex issue deserving IEA’s attention.”

Even under the most traditional interpretation of the IEA’s mandate, this bland statement is inadequate. Climate change is highly likely to make energy demand and supply more volatile and crisis-prone. Kissinger would have wanted the United States and its allies to be positioned not only to react to these probabilities, but to reduce them.

Of course, there are many ways to do that. Climate change is, indeed, extraordinarily complex. But surely, modeling pathways to eliminate the risk altogether, which the vast majority of nations in the world (including, intermittently, the United States) have pledged to do, should be among the IEA’s contributions to the debate. Its Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario (NZE) charts one such pathway. The model attempts to minimize the cost and volatility of the energy transition subject to numerous constraints, including ensuring energy security and achieving two of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development goals, universal energy access and a major reduction in air pollution.

Introducing the NZE pathway in 2021, Birol characterized it as “narrow and extremely challenging.” It has grown ever more so since then. The Barrasso report labels it “not credible.” Yet, as Bordoff points out, the NZE’s purpose is to show what policies would be required to achieve global goals. If their enactment and implementation are “staggeringly difficult”(in Bordoff’s words) or even impossible, the NZE should provide a guardrail against “magical thinking” about the transition. The only thing more magical than thinking the transition will be easy or costless, as I have long argued, would be to wish the need for it away by ignoring climate change and its consequences altogether.

To say that the NZE should provide a guardrail against magical thinking, however, does not mean that it does. Cleantech investors and climate campaigners have sometimes taken the scenario to be a scientific mandate for policy or even a forecast. The IEA has not always been clear enough about the purpose of its scenarios or sufficiently realistic in its framing of the challenge in realizing the NZE. The IEA’s more recent communications suggest that it has taken this aspect of the conservative critique to heart.

The agency would also do well to respond constructively to the criticism of the Stated Policies Scenario (SPS). This scenario incorporates the IEA’s judgments about which policies that governments have adopted are likely to be implemented, and which are not. By contrast, the Current Policies Scenario (CPS), which the IEA phased out in favor of the SPS, avoided such judgments. It simply assumed that current policies would continue indefinitely. The Barrasso report frames the judgments in the SPS as “bias” compared to the CPS’s “objective manner.”

That framing is unfair. All modeling incorporates judgments. The CPS’s judgment that all policies will be static indefinitely is, in the words of one modeler I spoke with, “certain to be wrong.” Another called it “ridiculous.” Even so, if IEA’s users, like McNally, want a “business as usual” scenario like the CPS, reviving it, as the IEA has recently promised to do, would add value to the agency’s work. The modelers noted that the IEA could also consider varying a number of other parameters, such as economic growth rates, which frequently have a bigger impact on outcomes than national energy and climate policies, to shed light on a wider range of possible futures.

In addition to adjusting its analytical approach in areas where the conservative critique rests on solid ground and communicating its analysis more carefully, the IEA could limit the damage that may be coming its way by emphasizing issues that Birol and Barrasso agree on. Supply chain analysis, for example, is applicable to all energy resources. The Barrasso report characterizes China’s dominant position in many energy technology supply chains as “intolerable.” Similarly, the report continues, “Russia’s dominance of supply chain for uranium conversion and enrichment services also merits the sustained attention of IEA.” The IEA explicitly added this issue to its mandate in 2022, and it has hosted a high-profile summit and initiated emergency planning, in addition to conducting research, since then.

Cybersecurity is a second common interest. China and Russia have built large hacking operations that have targeted energy systems in the United States and allied countries. Electricity systems, regardless of how they are powered, are more vulnerable to such attacks, due to their massive scale and relative openness. As electricity demand rises to power artificial intelligence (AI) and other new end uses, grids must, in parallel, become harder to hack. The IEA has long sought to focus attention on the necessity, opportunities, and risks of digitalization of the energy system, and it launched a major new AI initiative last year.

China’s central role in creating these energy security risks is a final theme that conservative critics in the United States should find appealing. An American pullback or withdrawal from the IEA could create more space for China to shape the agency’s activities. And, in the event of a crisis, the United States’ absence would not only weaken any coordinated actions to stabilize energy markets, but it might also enable China to shape the turmoil to benefit itself.

While responding constructively to the conservative critique, the IEA should not compromise on either the scope of its mission or the core content of its findings. The 2024 WEO appropriately calls for a “comprehensive approach to energy security,” the IEA’s “foundational and central mission.” That includes understanding the mutual interactions of energy and climate, which are “inextricably linked.”

Governments may not want to hear bad news, whether about the climate impacts of continued unabated use of fossil fuels or about the loss of oil revenue if the system changes course. But these hard truths are vital to sound, democratic decision-making. Indeed, “objectively informing and educating policymakers” is precisely what the Barrasso report calls on the IEA to do. If that puts the IEA in the line of fire, the agency may just have to take some bullets to advance this important cause.

David M. Hart is a senior fellow for climate and energy at the Council on Foreign Relations and professor emeritus of public policy at George Mason University’s Schar School.

Image: Shutterstock.com/T. Schneider