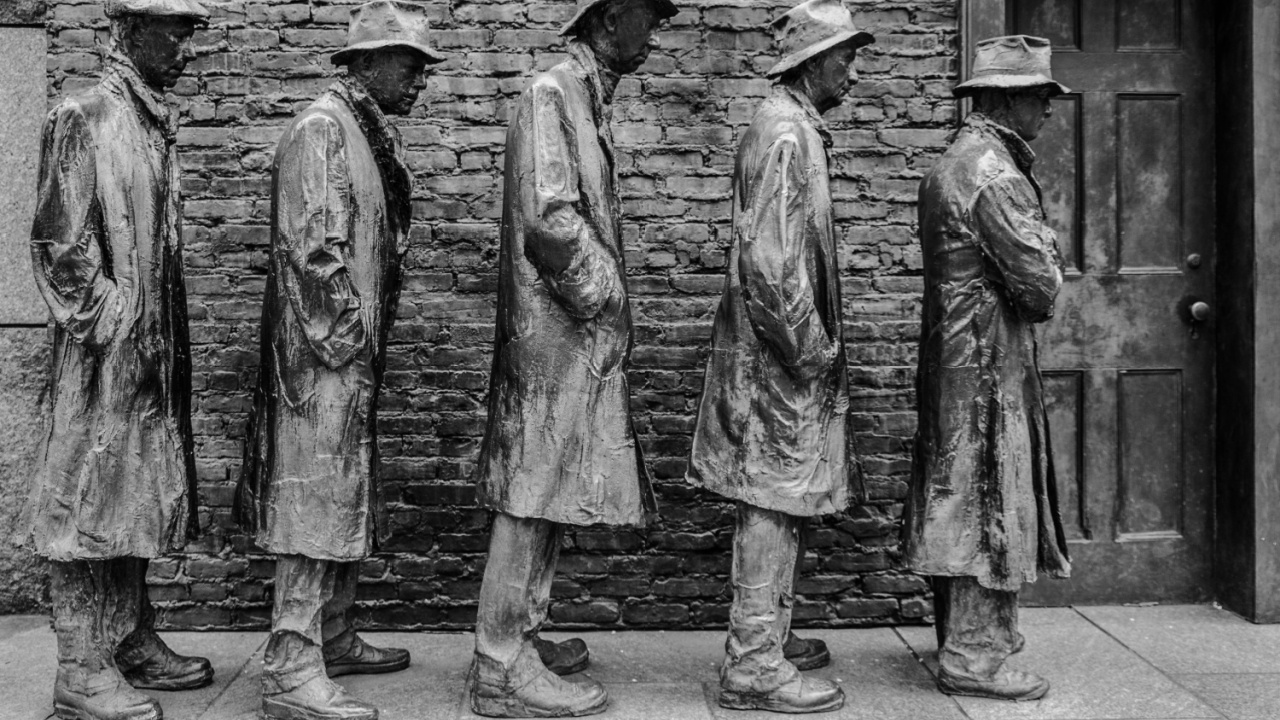

Tariffs and the Specter of Smoot-Hawley

Bad trade policy helped prolong the Great Depression. Even a muted repeat of this experience is terrifying.

Stock prices have tumbled, and anxieties have soared with the White House announcement of “reciprocal” tariffs. Violent as the market’s reaction has been, it should not have come as a surprise. Stocks had already given considerable ground in response to recessionary signs that had been emerging from the economy. Now with the president’s recent announcement, the terrible prospect of a trade war adds greatly to the mix of bad news.

Tariffs now rival those of the storied Smoot-Hawley Act that prompted massive retaliations and a global trade war in the 1930s, events that prolonged the Great Depression. Trump—always inscrutable—may have plans that can avoid such a terrible prospect, but however one parses this White House move, it is a risky business indeed.

From Trump’s earlier statements, it is hard to believe he wants to start a trade war. Even when he imposed tariffs on China in 2018 and 2019, he justified them as a way to get Beijing to rescind its very significant protectionist policies. He has justified these recent tariffs in the same way, suggesting that they are a great lever for negotiations. He implicitly makes this same claim by referring to these new tariffs as “reciprocal.”

That characterization suggests that other nations, rather than retaliating, can elevate the pressure of American tariffs by ending the practices to which Trump says he is responding. But even if, as he has suggested in the past, the goal is a negotiation that will reduce trade restraints, he nonetheless has put world trade and by extension the world economy in great jeopardy.

If other nations fail to pick up on Trump’s signal—if that is indeed what he is sending—then trade war, with all its economic ills, becomes likely. China has already retaliated with tariffs of 34 percent. If this is typical of the pattern unleashed by Trump’s announcement, then the world will begin to face something akin to the mess that American tariffs prompted in the 1930s.

After the stock market crash of 1929, the sudden rise in American unemployment greatly moved Senator Reed Smoot (R-UT) and Representative Willis Hawley (R-OR). To protect jobs in the United States, they shepherded an immense tariff bill through Congress. The Smoot-Hawley Act, as it is called, imposed an average levy of some 20 percent on some 20,000 imports. Immediately, other countries retaliated against American products with tariffs.

By 1933, U.S. imports and exports had fallen by two-thirds compared to their level in 1929. Though the legislation was repealed in 1934, it took years to unwind its global ill effects. It doubtless added considerably to the depth and duration of the Great Depression. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the rise in unemployment motivating the tariff legislation had by early 1930 risen to 8.7 percent of the workforce. Only after the legislation passed did joblessness rise to the terrible highs of nearly a quarter of the workforce in 1932 and 1933.

Even a much-muted version of this historical experience is a terrifying prospect. And it is along these lines, as well as orthodox economic theory, that much of the objection to Trump’s tariffs has stemmed. The problem for the general public, however, is that these same arguments were used to promote globalization from the 1990s through the 2010s.

And though the free-trade-free-capital-flows trend did enrich some, it also immiserated working men and women across the country. No doubt, this response to the tariff criticism has some weight within the Trump White House, and these recent measures are a way of reversing the trend that so hurt many of Trump’s constituents. Sadly, when a driver runs someone over with his car, it does not make things better to back over him.

Milton Ezrati is a contributing editor at The National Interest, an affiliate of the Center for the Study of Human Capital at the University at Buffalo (SUNY), and chief economist for Vested, the New York-based communications firm. His latest books are Thirty Tomorrows: The Next Three Decades of Globalization, Demographics, and How We Will Live and Bite-Sized Investing.

Image: Brian Logan Photography / Shutterstock.com.